Cavaliers AND LeBron AND Playoff

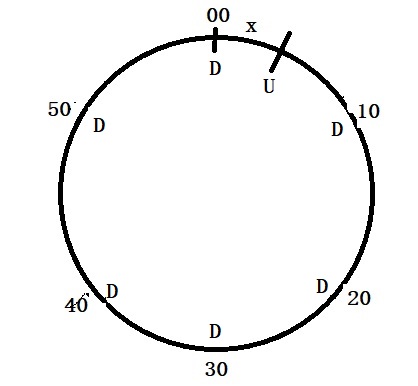

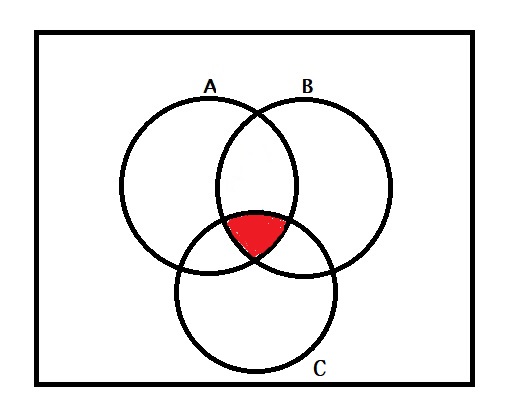

We have seen one extreme of the AND rule of probability, where people forget to realise how the conjunction makes events rarer. A well-known case is Linda’s problem. Here is the pictorial representation of the AND rule, which combines three events.

The shaded region shows the joint probability of A, B, and C. As the number of events increases, the ‘common area’ shrinks. There is another extreme case of conjunction fallacy, typically used by journalists. Read the following title that appeared in CBS Sports.

Cavaliers win first playoff series without LeBron James since 1993 by taking Game 7 over Magic

The writer has combined Cleaveland’s playoff entry, the first-round victory, and Lebron’s absence, making it a ‘rare’ sensational event.

1. Is this the first playoff entry? No, this young Cavaliers team has been playing well. They were also in the playoff last season (2022–23) but lost against the Nicks.

2. So this must be the first series win (ever)? No, they have recently made four consecutive NBA final appearances (2014-15, 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18). Note that these are not just one series victory; we are talking about championship finals—four times!

3. But this happened after a long time? No, the team won the first rounds in 2007-08, 2008-09 and 2009-10.

4. Then, how can I make it a rare event? Find things in common and start subtracting them. Win, Lebron, Decade, the list goes on.

Cavaliers AND LeBron AND Playoff Read More »