The New Study Reveals That

WebMD ran an article in 2008 titled Eating Breakfast May Beat Teen Obesity. The article caused quite a stir in the public domain. The original study, published in Pediatrics, focused on the dietary and weight patterns of 2,216 teenagers over five years (1998-2003) from public schools in Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota.

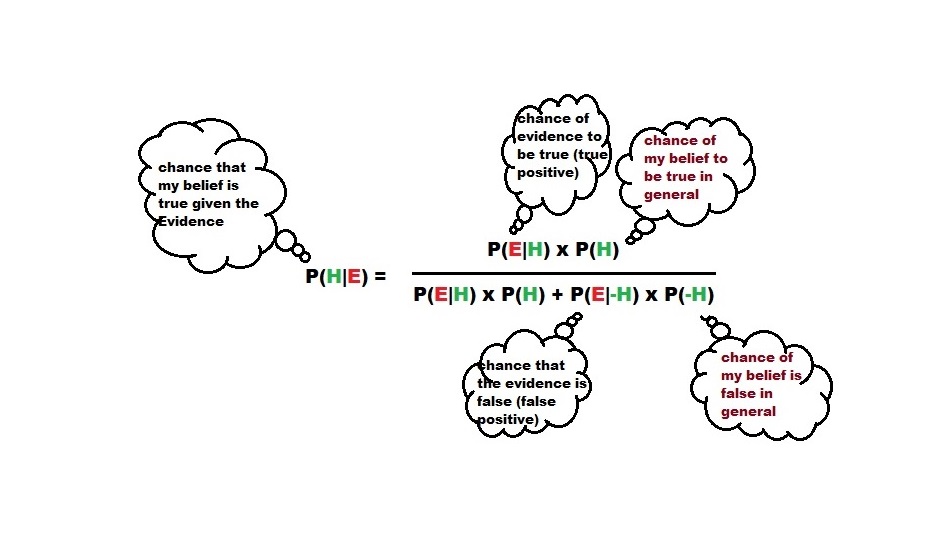

Did the study conclude that breakfast is a medicine for teenagers to fight against obesity? At least the title and the opening remarks gave that impression. Before jumping to a conclusion, let us examine the various possibilities.

Cause or a Coincidence?

The first possibility is that it could be a complete coincidence that those who ate breakfast gained less weight. That is an easy remark that one can pass to any such study.

What Other Reasons?

Think about possibilities that can make someone skip breakfast. Maybe she wakes up late and has no time to breakfast before school. This could be because she sleeps long or goes to bed late. What about the eating habits of people who sleep late at night? The late sleepers may pack their meal with more or multiple sets of food.

What about some of them skipping breakfast because they were already obese (for any other reasons) and wished to cut some calories (cause and outcome reversed)?

How important are the study location, socioeconomic background, and education levels? As per the CDC, even in the US, obesity is lower among people with lower and higher income but higher in middle-income groups. What could be the outcome had the research been conducted in India, Australia, The Netherlands, or the Republic of Congo?

Or Just a Correlation?

Would the conclusions have differed if the researchers had examined their lunch, dinner, or snack habits? WebMD leaves some clues.

“A new study shows teenagers who eat breakfast regularly eat a healthier diet and are more physically active throughout their adolescence than those who skip breakfast”.

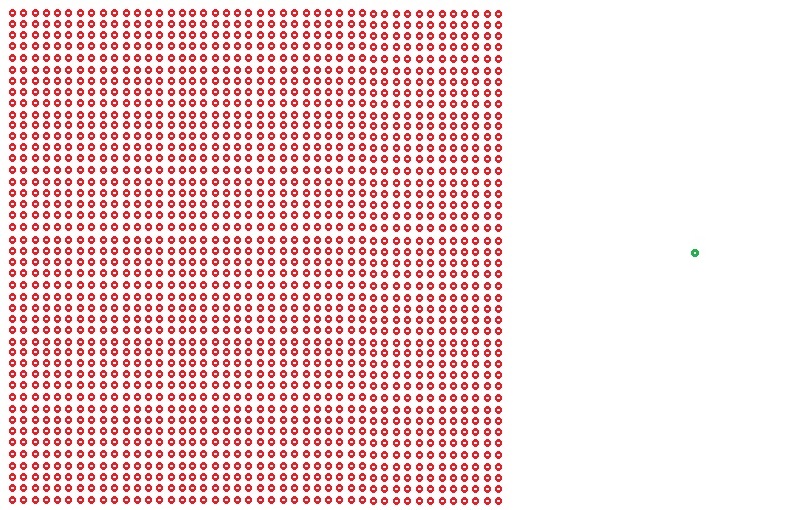

So it is not just eating breakfast, but a set of other things, or confounding factors, are also important. The first word to notice is regularly, which suggests certain habits. The second one is more physically active, and the third is a healthier diet, which may include more fibre and less fat. We know cutting excessive fat consumption and regular exercise leads to weight loss.

There are many possible explanations to explain this correlation other than a simplistic statement for weight loss. In statistics, these are confounding variables, which happen when a common cause gives out multiple results, leading to the confusion that one of the outcomes is caused by the other.

Adult Obesity: CDC

The New Study Reveals That Read More »