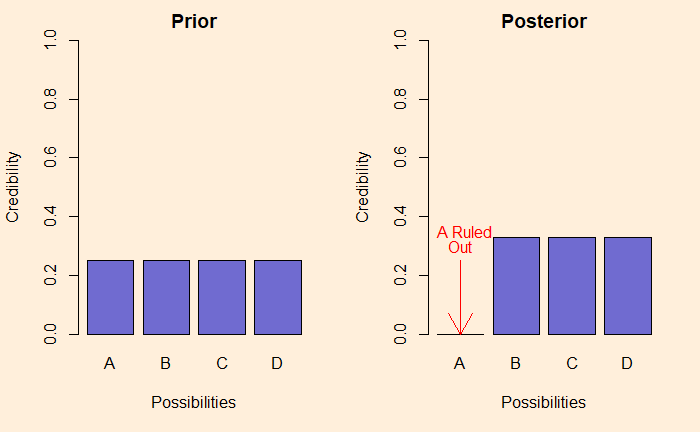

We started with the equation of life, Bayes’ theorem, how it mimics the natural learning process, and how even experts can not escape the curse of the base rate fallacy.

We understood the law of large numbers but failed to notice that there was no law of small numbers and continued gambling, hoping to even out, leading to complete ruin.

We have learned mathematically that at the Roulette table, the house always wins, yet we spent countless minutes watching YouTube videos learning strategies to beat the wheel. We also watched financial analysts all day on TV, reasoning on hindsight and glorifying market-beating fund managers, forgetting they were just the survivors of Russian roulette. The same people continue to make us believe in momentum and hot hands.

People gamble and play the lottery, where they are guaranteed to lose, and fail to invest for their retirement, where they are guaranteed to win. Three-quarters of Americans believe in at least one phenomenon that defines the law of physics, including psychic healing (55 per cent), extrasensory perception (41 per cent), haunted houses (37 per cent), and ghosts (32 per cent).

Rationality, by Steven Pinker

We have seen how journalism can mesmerise readers by reporting an 86% increase in myocarditis for the vaccinated, a 300% increase in thrombosis over oral contraceptives, or an 18% risk of colorectal cancer by eating processed meat. We just became easy prey for our inability to make decisions based on risk-benefit trade-offs and the eternal confusion between absolute and relative risks.

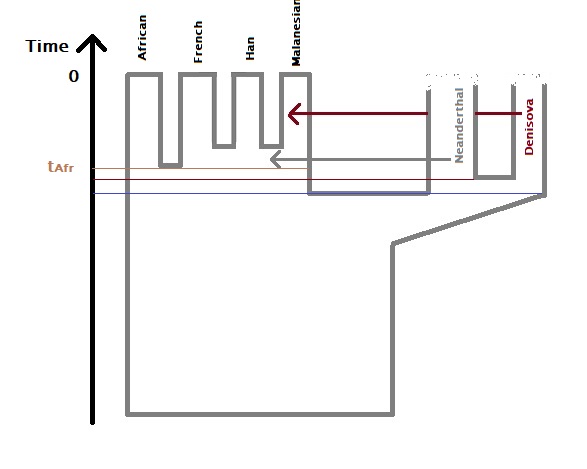

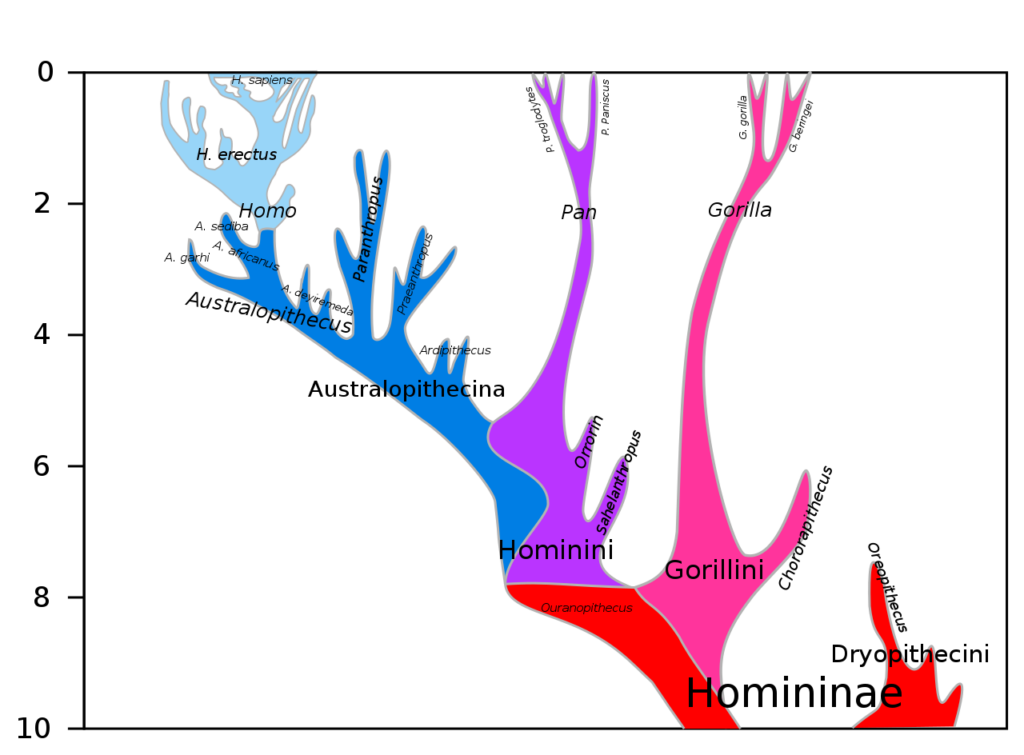

We found how the world can make us believe in diseases with causes and designs with a purpose when events were nothing but random processes. We see how careless choice of words and phrases and incorrect teaching lead to myths about evolution.

Even in an era of open data, data science and data journalism, we still need basic statistical principles in order not to be misled by apparent patterns in the numbers.

The Art of Statistics: How to Learn from Data, by David Spiegelhalter

The author was referring to variabilities in the observed rates of events when the population is small, which is the concept behind funnel plots.

We understand that international trade is a win-win for both parties, yet we let free rein to populism and Brexit. We know that the Muslim community in India is on the fastest downhill in the fertility curve, yet we want to believe that the opposite is true and continue believing in one-child policies.

We also know that life is not a zero-sum game and that probability theory is not another useless thing you study in schools and forget later, but it is about how we make decisions and appreciate life. The understanding, or the lack of it, can be a choice between life and death, as we have just witnessed in the global pandemic.

Could everyone have a fact-based worldview one day? Big change is always difficult to imagine. But it is definitely possible, and I think it will happen, for two simple reasons. First: a fact-based worldview is more useful for navigating life, just like an accurate GPS is more useful for finding your way in the city. Second, and probably more important: a fact-based worldview is more comfortable.

Factfulness, by Hans Rosling with Anna Rosling Rönnlund and Ola Rosling