The story of returning warplanes from world war II presents the finest example of understanding survivorship bias. Here it goes.

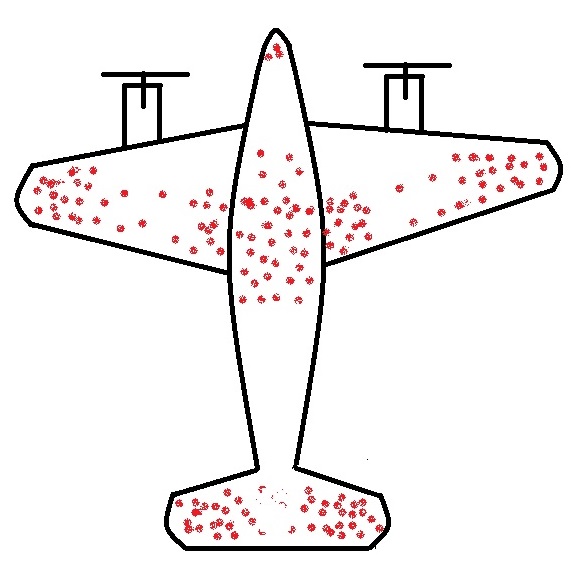

When the US military had a chance to look at the fighter planes that came back from the battlefield, they observed some patterns. They found that the bullet marks on the planes were not uniform. Instead, it had denser patches on the fuselage and fewer spots on, say, engines, cockpit or some of the weaker parts – roughly what you see on the sketch below.

The idea was to use the data to optimise armouring the planes to sufficiently make the aircraft safer without adding too much weight that reduces the range.

So the statistical Research Group (SRG) was assembled to devise the strategy. Abraham Wald was the leading statistician who came up with this counterintuitive advice: the armour will not be where the holes are, but it will be where there are none. Because the planes with holes in those spots were shot down and never came back!

Survivors will mislead you

This is the classical survivorship bias. In the field, the planes were shot all over. The surviving ones presented one pattern; the unlucky ones would have shown the opposite.

Abraham Wald and the Missing Bullet Holes

Survivorship Bias: Eddie Woo