Well, I don’t think there is anything wrong with it! They are like the carbon tax and the cap and trade – means to charge the emitter their share of the social cost of carbon.

But what are fuel standards? These are regulations set by the government targeting to cut down CO2 emissions. For example, the US CAFE standards (corporate average fuel economy) required each manufacturer to meet two specified fleet average fuel economy levels for cars and light trucks, respectively. California pioneered the low carbon fuel standard that regulates the average carbon content per gallon of gasoline. If the former controls the amount one can burn, the latter focuses on capping the CO2 in the given amount of fuel.

Let’s understand how a fuel efficiency standard operates.

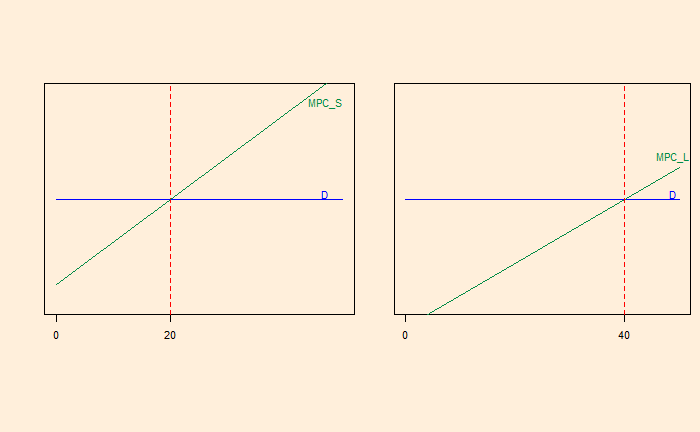

Suppose a manufacturer sells 20 small cars (S) and 40 large cars (L). Let the economies of these cards be 30 miles per gallon (mpg) for S and 10 mpg for L. The administration requires the average mpg (of the car sold) to be 20 mpg. On a simplistic level, this allows the company to sell one S for every L [(30 + 10) / 2 = 20 mpg]. Let’s look at a simplified supply-demand curve.

MPC = Marginal Private Cost or the change in the producer’s total cost brought about by the production of an additional unit. The flat demand curve means it is perfectly competitive.

Naturally, this must change as per regulation because the average mpg is (20 x 30 + 40 x 10) / 60 = 16.7; less than 20. One solution is to reduce L production to 20 and bring the mpg to the compliance level.

The shaded triangle on the right is the amount of profit that is forfeited in this exercise. What happens if I sell five more Ls? It would mean the company must sell five more Ss at a loss.

This process can go on until the red-shaded area on the left matches with the green-shaded area on the right. That means the S car sales increase.

So, a performance standard subsidises the product, which makes the standard easier. In other words, the firm taxes the poor-performing car by subsidising the better performer. The plot will tell you that L is sold at a price higher than its marginal cost, whereas S is sold below its marginal cost.

So, what is wrong with fuel standards? There is a possibility that the firm ends up selling more cars than it would do otherwise. There is also a possibility for the Jevons paradox, where people end up driving the fuel-efficient car more (rebound).