Does rational decision-making exist? Well, that depends on how you define it. We have seen the expected value and expected utility theories. The expected value is a straightforward multiplication between the value of an option and its probability to be realised. In this scheme, a 20% chance for $600 (0.2 x $600 = $120) is a clear winner over a sure $100. But we know that is not an automatic choice for people. If one finds more utility for $100, a sure chance is worth more than the possibility of $600; remember, if you are among the lucky 20%, you get $600, not $120. At the same time, a gambler may go for not just %600 but even $400!

These two rules are still not enough to categorise all choices. There is another principle that governs choice, known as the reference-dependent model. i.e. an individual’s preference is dependent on the asset she already possesses. Driven by psychology, a sort of inertia creeps in such situations.

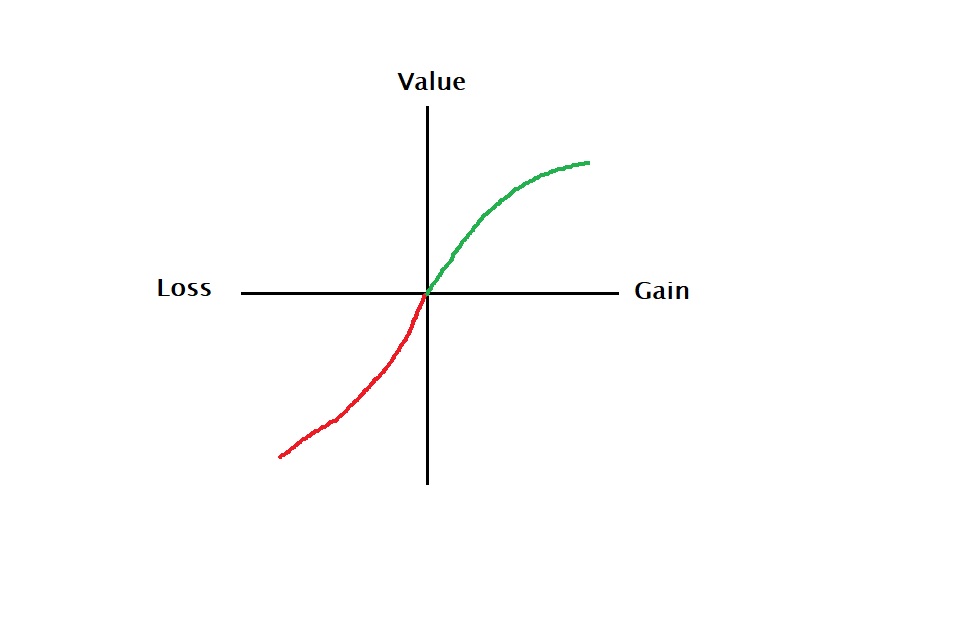

Loss aversion is one such instance. It means that the perceived downside appears heavier than the potential upsides for someone possessing a material (reference point). As a result, you decide to stay where you are – a case of status quo bias. Tversky and Kahneman sketch this value function in the following form.

There is data available from field studies on the choice of medical plans. The researchers found that a new medical scheme is more likely chosen by a new employee than someone hired before that plan was available.

Tversky and Kahneman, “Loss Aversion and Riskless Choice: A Reference Dependent Model,” Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 1991