We all like to see justice happening in every trial. What is justice? In simple language, it is the conviction of the guilty and the acquittal of the innocent. In the court, jurors encounter facts, testimonies, arguments in support and against the defendant. The number and variety of evidence make them feel like random, independent events and make the hypothesis (that the accused is guilty or not) in front of the judge a distribution!

Overlapping Evidence

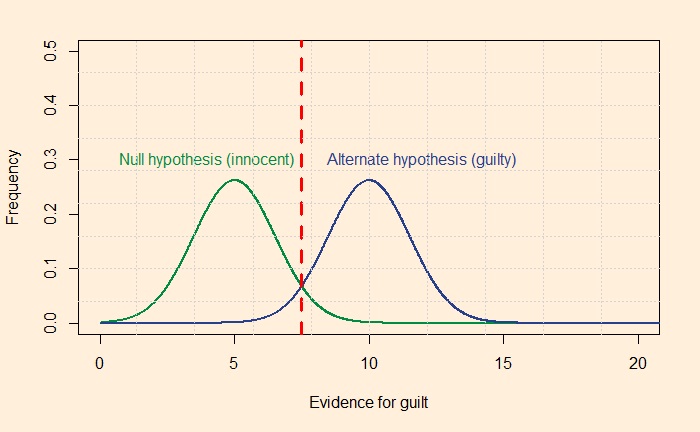

To illustrate the complexity of decision making, see the following two distributions (I chose uniform distribution as an example).

You can imagine four possibilities formed by such overlapping curves. The right-hand side tail of the innocent line (green) that enters the guilty (blue) region leads to the conviction of the innocent. The opposite – acquittal of the guilty – happens for the left-hand side tail of the guilty line that enters the non-guilty. The dotted line at the crossover of the two curves represents the default position of the decision or the point of optimal justice. At that junction, there are equal frequencies for false alarms and misses.

10 guilty for 1 innocent

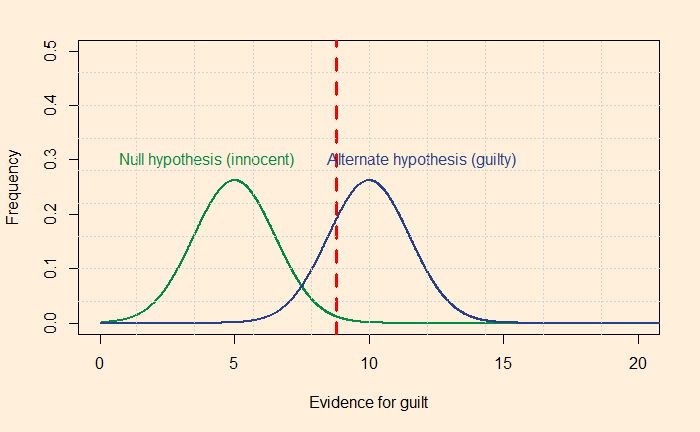

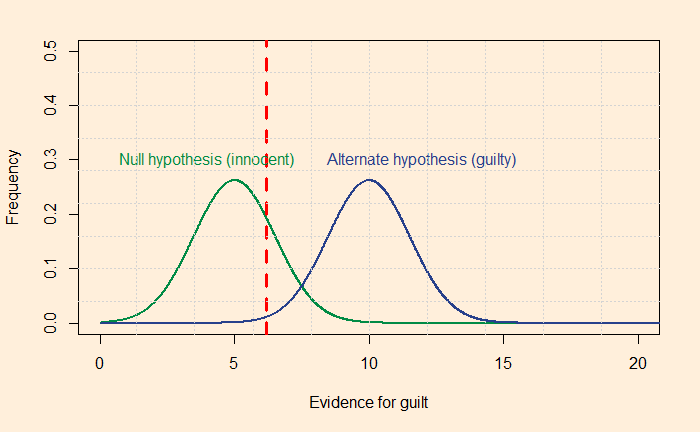

If the judge believes in Blackstone’s formulation, she will move her position to the right, as in the following plot.

The jury is willing to miss more guilty but assure fewer innocents are convicted. The opposite will happen if there is a zero-tolerance policy for the guilty; the examples in the real world are many, especially when it comes to crimes against national interest.

Errors and mitigations

So, what can jurors do to reduce the number of errors? We will look at more theoretical treatments and suggestions in the next post.

Do juries meet our expectations?: Arkes and Mellers