This is not a post against health screening. In fact, I did my annual checkup yesterday, something I’ve been maintaining since my 30s. Today, we critically examine a few potential challenges associated with the much-advertised benefits of cancer screening.

Survival rates

The most common metric of reporting is the survival rate. It’s the percentage population who are diagnosed with an illness that survives a particular period. Based on the local system, these periods maybe five years, ten years etc.

A long-term (2019-2013) study of prostate cancer from a French administrative entity was reported by Bellier et al. The results show the following features. The incident rate remained almost flat at around 850 per 100,000 from 1991 to 2003 for people aged 75 and over. Then the rate started decreasing at an annual rate of 7%. For the men aged 60-74, 1991 to 2005 showed a steady increase followed by a decrease similar to the older age. Overall, the younger group (60-74) had a higher 8-year survival rate (as high as 95%).

Lead time bias

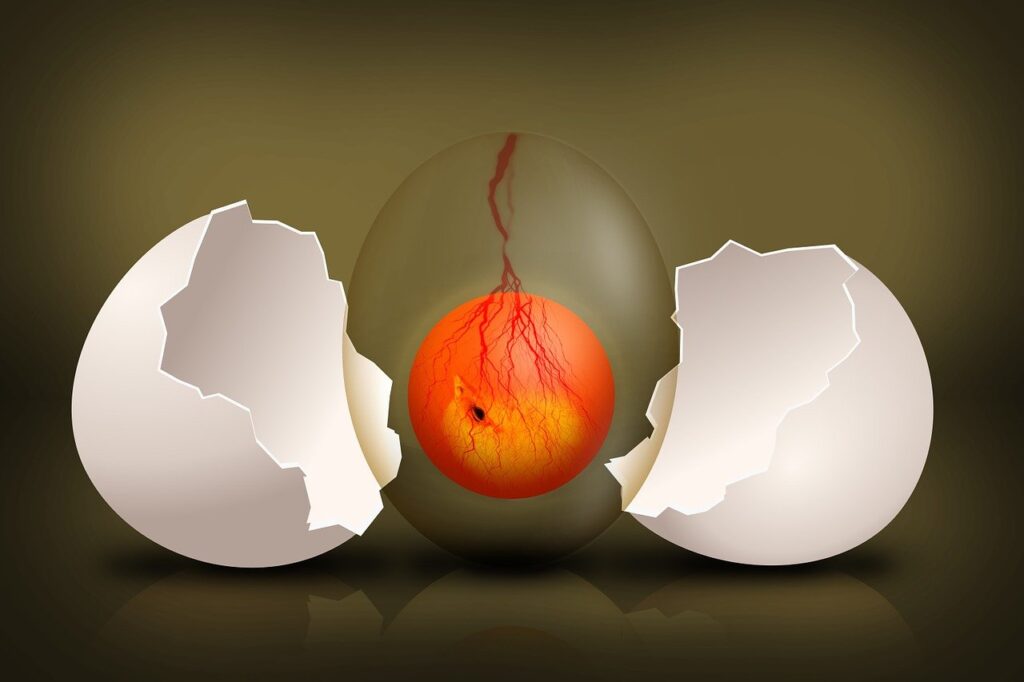

Illnesses such as cancers have a particular pre-clinical phase, the time lag between the onset of disease and the appearance of symptoms. A screening test can catch the disease at this stage. The longer the pre-clinical phase, the higher the likelihood of catching early by testing. This creates a lead time in comparison with the untested. Even if the ultimate year of death is the same, the lead time adds to the statistics giving a false impression of survival rates.

Overdiagnosis

Overdiagnosis is the detection of an illness that would not have resulted in symptoms and death. As the screening rate increases, followed by treatment of the positives, it becomes difficult to know how many of them benefitted from the treatment.

Confounding

Confounding also comes to complicate the analysis. In the last few decades, along with advancements in diagnostic techniques, cancer treatments have also improved significantly, leading to higher survival chances for the early and late-diagnosed population. It makes the separation of benefits of early diagnosis less apparent.