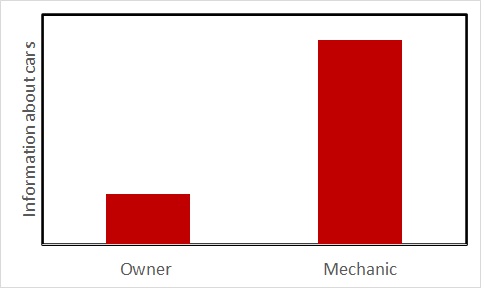

We have seen it before; information asymmetry leads to what is known as a principal-agent problem.

Take the popular example of the conflict between the car owner and the mechanic. You, a car owner, want to check the vehicle for annual maintenance. Under normal circumstances, unless the owner knows all about the car mechanics, a mechanic knows more about the car repair.

While the whole point of going to the workshop and what is expected from a mechanic both emanate from this (asymmetric) information, it can potentially develop a principal (car owner) agent (mechanic) problem.

You assume that the mechanic will use the information to exploit you by selling unnecessary parts and services. It happens because the incentives of the two parties (the principal and agent) are not the same and possibly conflicting. The owner wants to repair the car at a minimum cost, and the agent wants to maximise his return. In the end, a Moral Hazard is created. A moral hazard is an adverse behaviour that is encouraged by the situation.

Solutions to Moral Hazard

The easiest way is for the owner to gain more information. It may come from taking a ‘second opinion’ from another mechanic (who may have a different incentive) or an auto consultant (who may not even have an incentive).

The second is to reduce the incentive that the agent has. An example is the rating system, preferably at a neutral site, that can deter the agent from ripping the customer off.